Contemporary artists have continued the centuries-old impulse for Realism, as manifested by their close observation (“from” and “after” nature) of the natural world. This exhibition of selected artwork on paper posits a new definition of such Realism, realism that goes beyond the literal and seeks to go beyond the visible, illustrating humanity’s constant urge to measure its place in the world of figures and landscapes. Our choice of artists encompasses a range of contemporaries who explore the traditional subject matter that endures in modern and postmodern reconfigurations-- such as the nude, the portrait, and the landscape. These works create new connections with the exquisite examples of 19th/ 20th century drawings that show how artists of the past were also exploring beyond the visible while depicting the same themes.

An essay by curator Jovana Stokic is available below.

Park Avenue Armory

Park Avenue at 67th Street

New York City

Hours

Thursday - Friday: 12 to 8pm

Saturday: 12 to 7pm

Sunday: 12 to 5pm

Benefit Preview, Wednesday, November 2, 2022

Please join us for a curator-led conversation about the works on view with Jovana Stokic, PhD on Sunday, November 6 at 1:00 pm.

For tickets, please click here.

It is the actual act of drawing that forces the artist to look at the object in front of him, to dissect it in his mind’s eye and put it together again; or, if he is drawing from memory, that forces him to dredge his own mind, to discover the content of his own store of past observations.

John Berger (British art critic, painter, poet), 1953

Contemporary artists have continued the centuries-old impulse for Realism, as manifested by their close observation (“from” and “after” nature) of the natural world. This exhibition of selected artwork on paper posits a new definition of such Realism, realism that goes beyond the literal and seeks to go beyond the visible, illustrating humanity’s constant urge to measure its place in the world of figures and landscapes. Our choice of artists encompasses a range of contemporaries who explore the traditional subject matter that endures in modern and postmodern reconfigurations-- such as the nude, the portrait, and the landscape. These works create new connections with the exquisite examples of 19th/20th century drawings that show how artists of the past were also exploring beyond the visible while depicting the same themes.

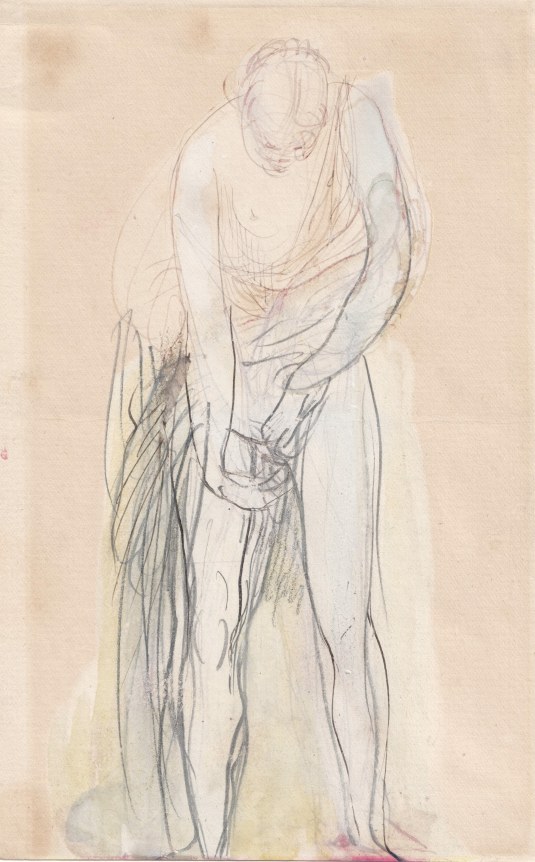

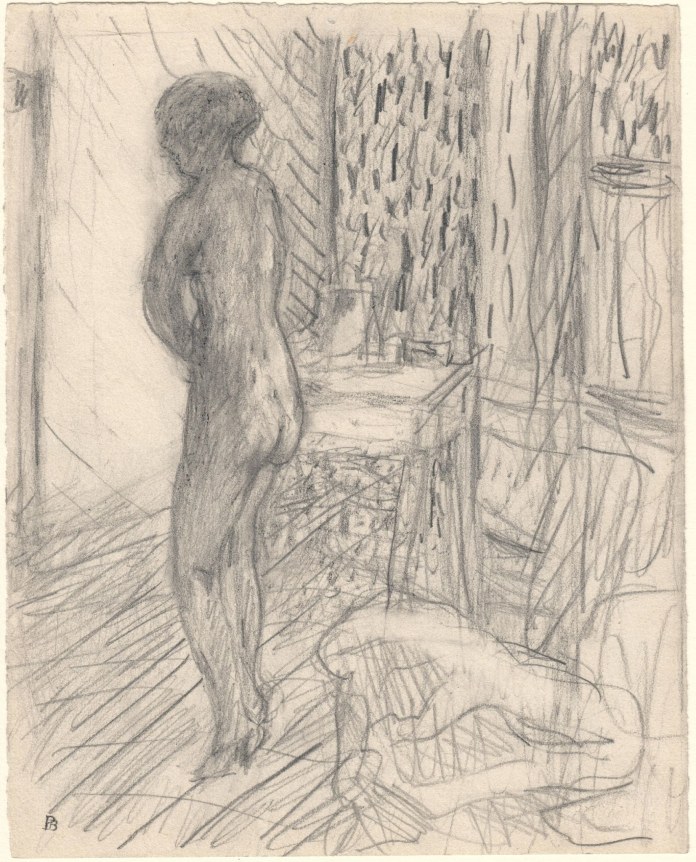

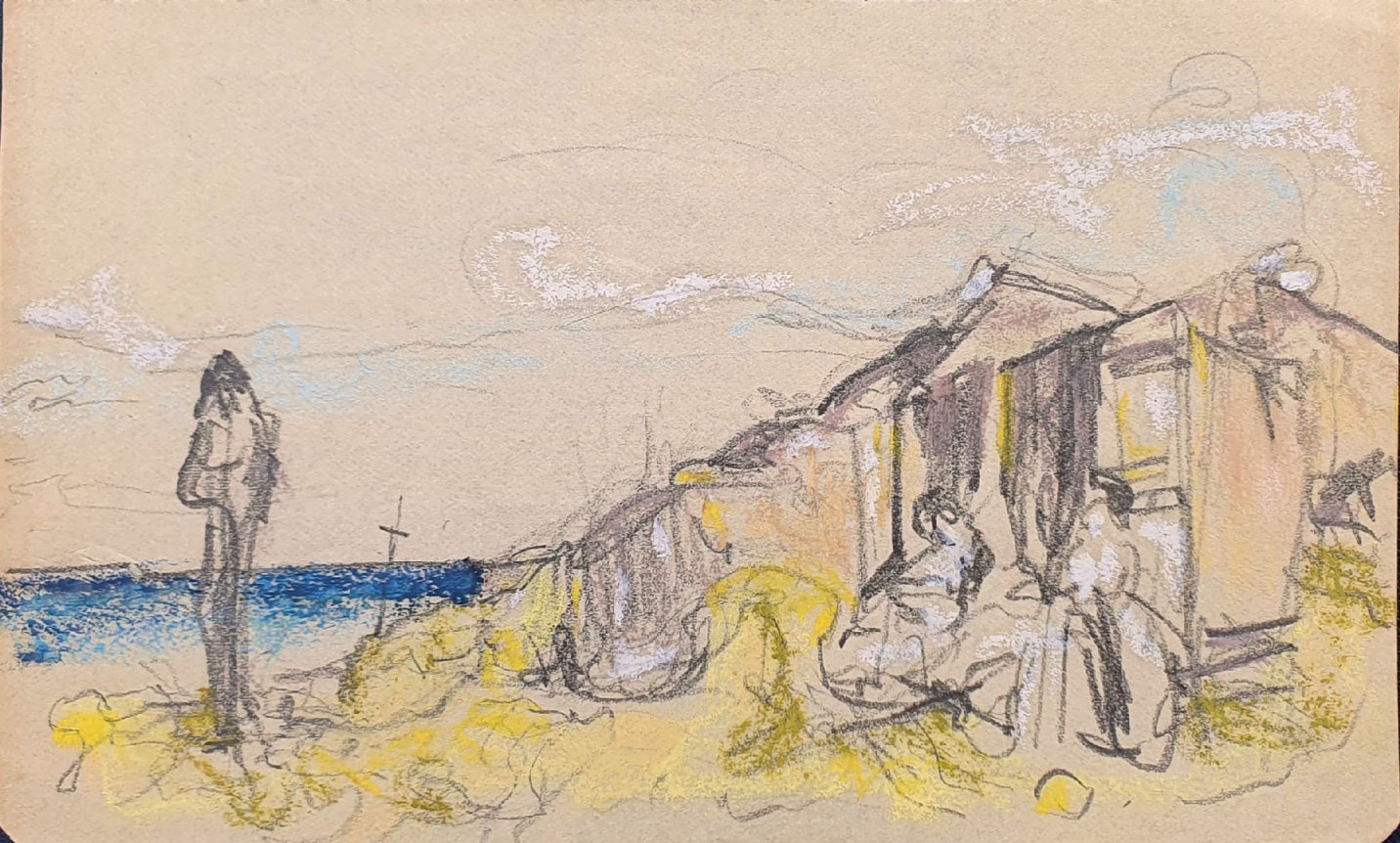

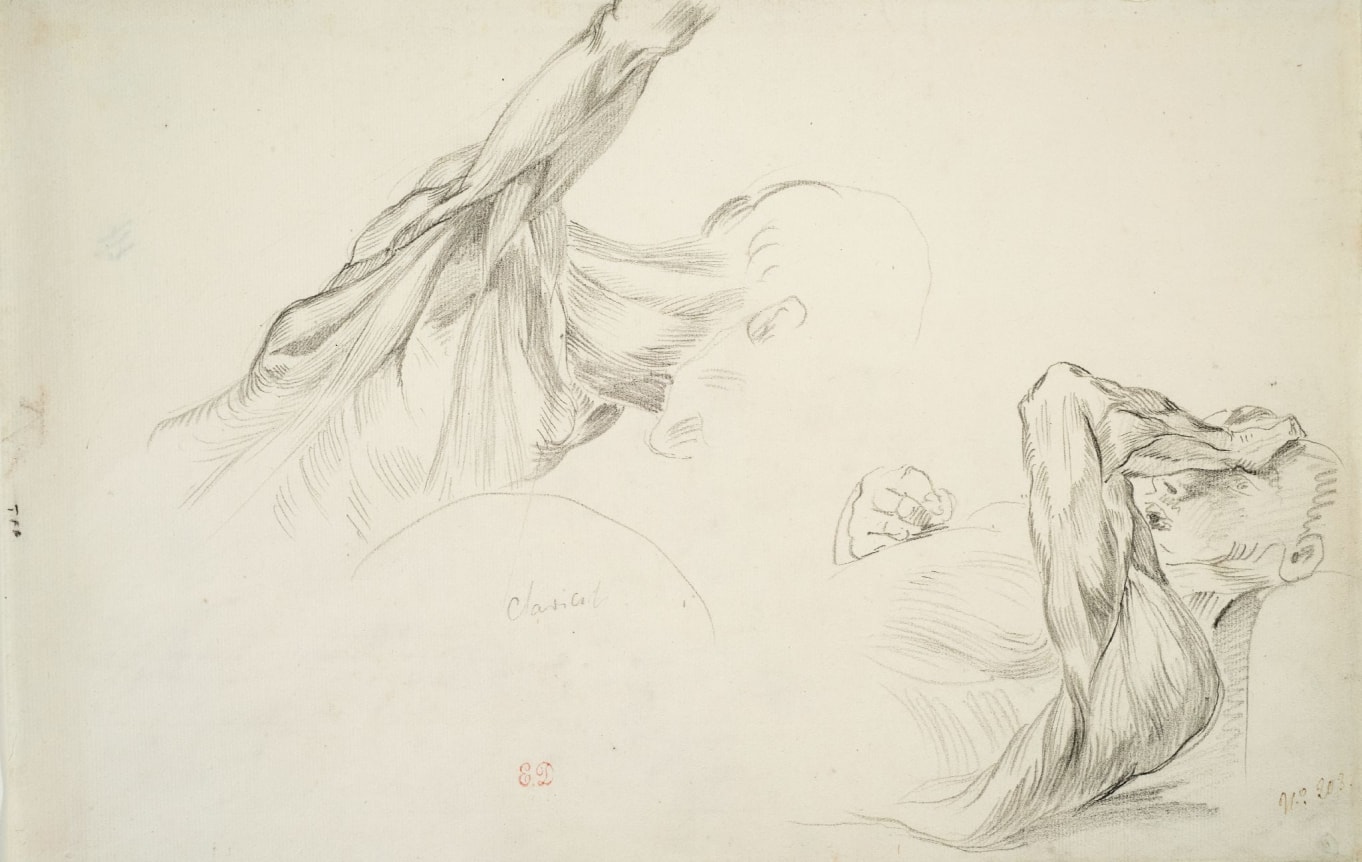

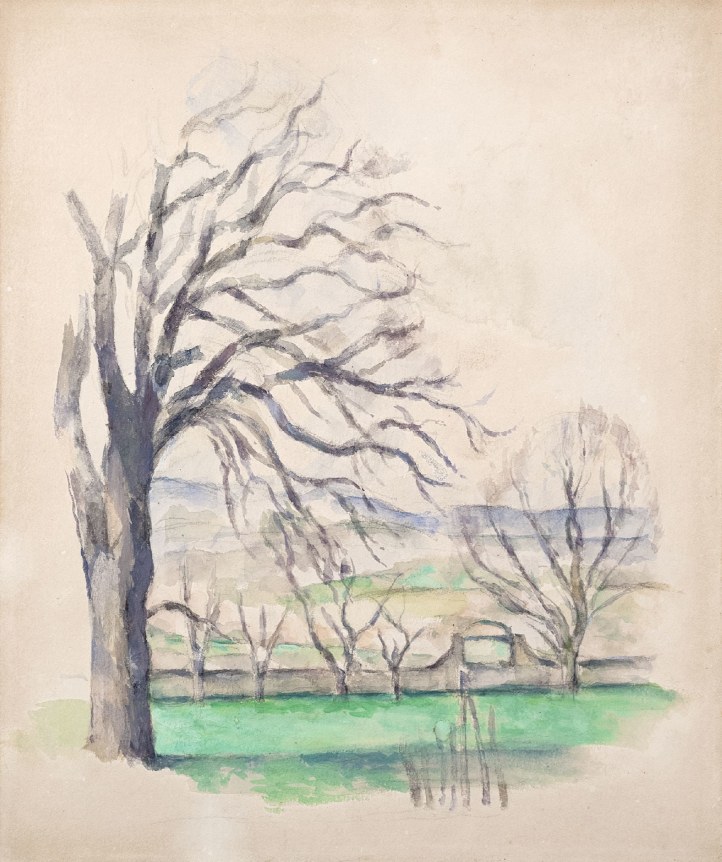

Until the early 20th century, artists had a more literal relationship with what they saw, which is evident in the variety of ways they re-envisioned it in their artwork. Paintings by Corot, Delacroix, Bonnard and Cezanne were finished representations of reality in one form or the other, varying in the degree of finish, but based on images from life. It was primarily in the works of art on paper that such artists allowed themselves to veer to the abstract: by showing partial views of what they were looking at (Signac); by flattening out the picture plane (Corot); or by placing separate studies on a sheet of paper in a way that makes it more emotionally powerful (Delacroix). Rodin, for example, in his late drawings would keep his eyes only on a moving model and not even look at the sheet of paper, in an effort to draw more freely. However, in all of these cases, it is important to recognize these drawings as finished works in and of themselves, and to understand how this non-literal approach reveals the emotional reality of the moment in which each was made. And while each work began as an act of direct observation, and is a complete work of art in and of itself, some were also used as records of memory, inspiring larger more defined works in other media.

With twenty-five works on paper of landscape, nude and portrait subject matter from Gericault and Delacroix and Cezanne and Bonnard and Vuillard to Peyton and Doig, our show will examine the role of emotions and memory within the realist impulse of looking. This selection of works on paper is heterogeneous – it contains studies of both the figure and the landscape in nature. Yet what connects the disparity in these works done over two centuries is the realist impulse to convey reality beyond imitation.

Matthew Barney’s latest body of work titled Redoubt is centered around a feature-length film set in Idaho’s Sawtooth Mountain Range. Barney’s life-long practice of observation of Nature points to both the interior and exterior aspect of landscape:

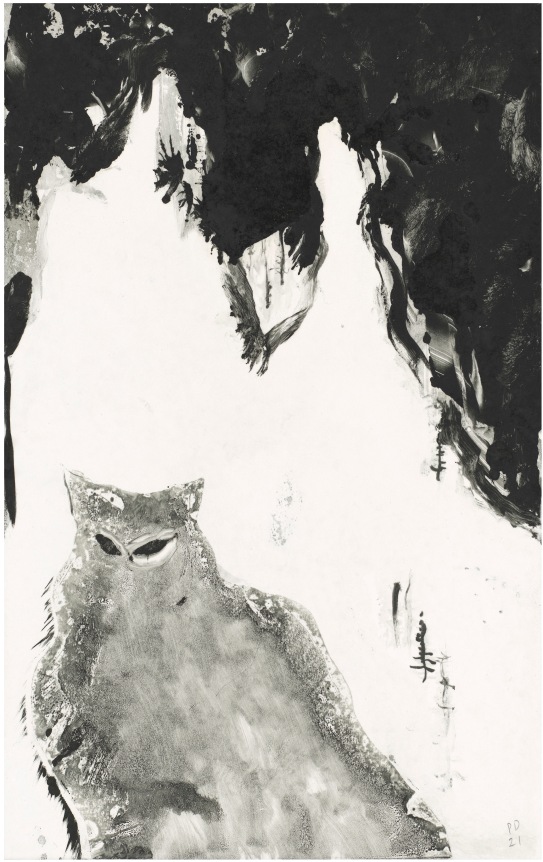

Peter Doig’s latest cycle of monotypes Untitled (Zermatt) of 2021 problematize the role of memory in the context of the depiction of nature in a guise of traditional landscape. His approach to depicting nature has a lot to do with his understanding of working of memory and psycho-geography. Doig frequently draws inspiration from his memories, but the blurred, ethereal quality of his images reflect the vagaries of time and processes of recollection. He balances the sense of the late twentieth and early twenty-first century painting with his acute relationship with painterly traditions of landscape painting. It is said that his style has introduced an existential dimension, prompting the viewer to ask questions about the picture itself, the world it represents, and our own place within the world.

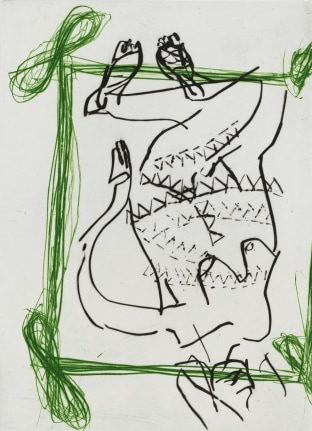

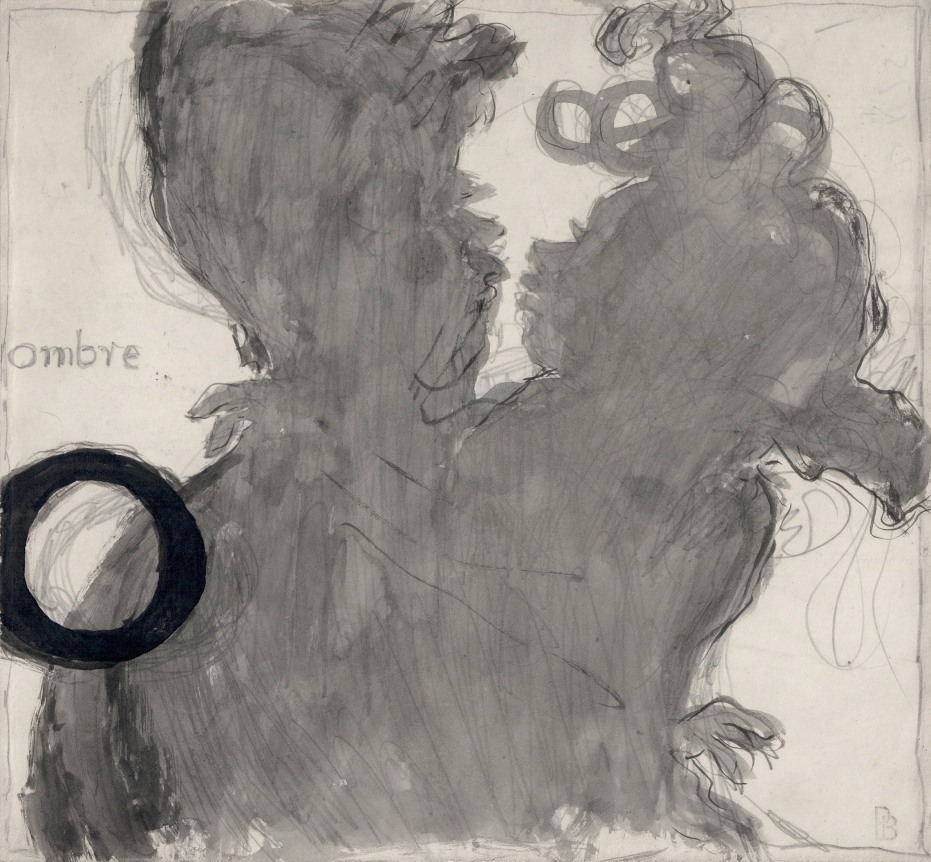

Having made almost one thousand prints in the course of his long career, Georg Baselitz stands out by his direct engagement with technical processes. This etching on paper is a compelling demonstration of Baselitz’s practice of the 1990s, exemplifying the artist’s experimentation with his signature upside-down figure that he had introduced in 1969. His raw scrawled inverted bodies with primal power and urgency reveal his preoccupation with the human fragility. Baselitz’s frequent treatment of the female body as a trope in the tradition of figurative art reveals his experimentations of the recurring use of gesture and perspective.

The artist explained:

“you need lines and hatching to put together what you want to represent, a body, for example. The extreme anti-naturalism that comes to bear in this was what interested me. This can be in the excessiveness, the elongation, the gnarlification, the ornamental in the sheets, but it can also be in the sensuality, that is, the allure created through engraving, meaning that you leave behind that which is tied to the subject…”

Joan Semmel moved to figuration in the 1970s out of her feminist concerns around the representation of women in the culture. Her practice traces the transformation that women’s sexuality has seen in the last century and emphasizes the possibility for female autonomy through the body. Semmel’s recent drawings continue her decades-long engagement with her own naked body as subject but from an approach of improvisational gesture. While her paintings are worked up in layers of color with diverse approaches to paint handling, the drawings place primacy on the immediacy of oil crayon on paper. With the emphasis on line, Semmel concentrates on the form of the figure, and on the broad range of shapes that it comprises.

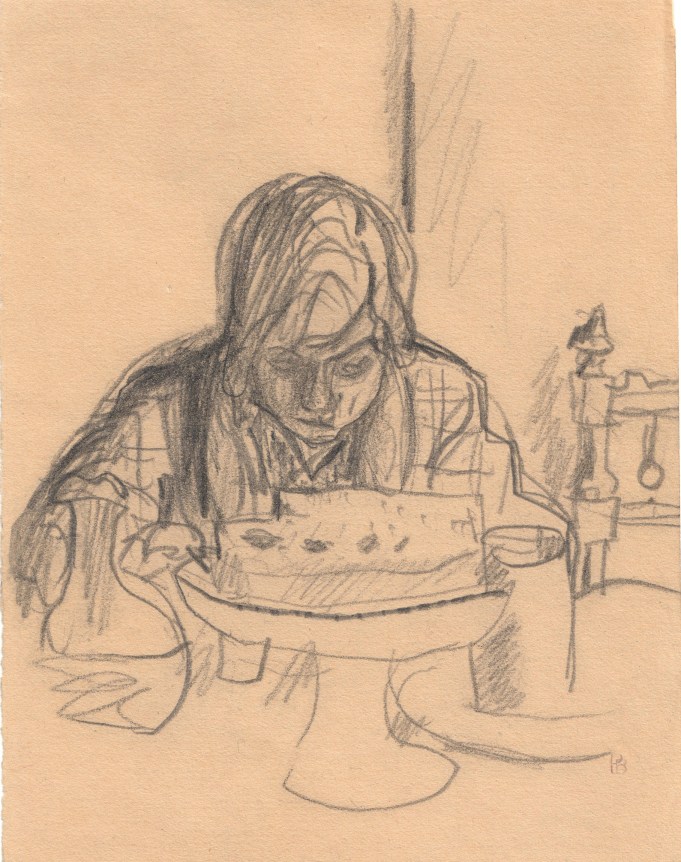

Elizabeth Peyton’s delicate small-scale portraits of celebrities, friends, and historical figures have a romantic sensibility that takes its cue from Delacroix’s intimate portrayals of sitters such as Chopin and George Sand. Her contrast between overt simplicity and representational complexity exaggerates the subtle space between celebrity and personhood, and the act of looking and being looked at; many of her paintings are of people in intimate, private spaces—at home reading or in bed sleeping, for instance—and are modeled after photographs or pre-existing artworks. Peyton paintings and drawings thus become repositories of emotional memory, evocation of the past, and subjectivity.

Gallery Description:

Jill Newhouse Gallery specializes in works on paper of all periods with a focus on 19th and 20th century European artists. The Realist Impulse is the latest in a series of exhibitions organized by the gallery pairing master artists with the art of today. Eugène Delacroix: The Enduring Power of Image (2019; essay by Jovana Stokic); Pierre Bonnard: Affinities (2018; essay by Karen Wilkin) and Under the Influence: Edouard Vuillard and Contemporary Art (2017; essay by Norman Kleeblatt) were also presented at the Art Show.