Jill Newhouse Gallery presents

Drawings 1830-1940

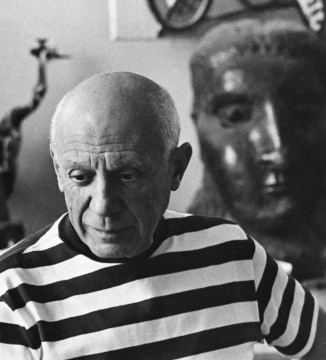

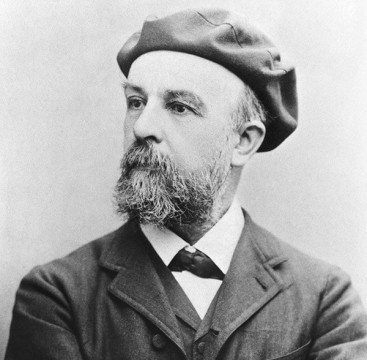

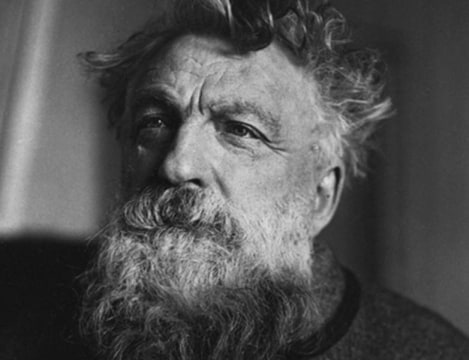

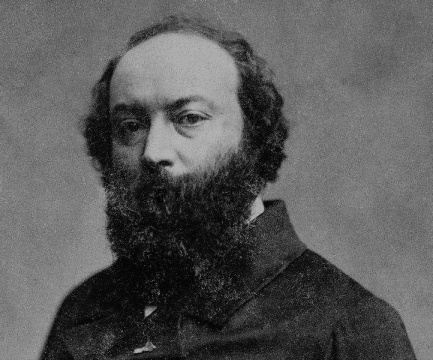

Corot, Delacroix, Ingres, Matisse, Picasso, Cézanne

(Including works by Barye, Carles, Harpignies, Jongkind, Klimt, Millet, Rousseau, Redon, Rodin, Sisley, Vuillard, and others)

January 20 - March 3

“What is the root word of drawing?

Etymology: From Middle English drawen, draȝen, dragen (“to drag, pull, push, draw (out), go to, make, add, etc.”)

From Old English dragan,

From Proto-West Germanic *dragan, from Proto-Germanic *draganą, from Proto-IndoEuropean *dʰregʰ- (“to draw, pull”).”

The word drawing is used to describe artworks made with various media such as pencil, chalk, or charcoal, done on a support usually understood to be paper. At this very particular moment in time, when computer generated art works are set to challenge the very definition and use of art and of drawing, we thought it would be important to revisit this most basic art form, as used by the most important artists of the 19th and 20th centuries.

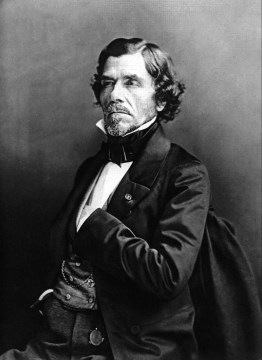

Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) was the leader of the French Romantic school of painting, and a prolific and creative draughtsman. One of the few artists who knew no limits to the subject matter of his work, he was a constant draughtsman in pencil, watercolor, and charcoal. He used drawing as a method of observation and as a memory tool in preserving images to create later painted compositions. Delacroix is represented here with several works, first an early study of a Greek Sculpted Head, done in charcoal with white heightening. This undated depiction compares closely to a large sheet in the collection of the Louvre depicting a long haired woman gazing down. The soft matted-down quality of the charcoal, highlighted by white chalk, is the same as in our work. The full frontal positioning of the face of the sculpture brings the personality of the sitter squarely in view and creates a powerful image.

Delacroix’s Dancer, is specifically datable to Delacroix’s trip as a diplomatic envoy to Morocco in January 1832, and depicts a young Jewish dancer in full costume, with her veils and scarfs fluttering around her. It is a page from one of a handful of rare sketchbooks Delacroix made on the trip where, denied by local protocol to view or depict Arab women, he used Jewish women instead as his models. He even attended a Jewish wedding where he made this drawing, later used to create the central figure in his important 1841 painting of the same title. Here the medium is pencil and the numerous color notes and inscriptions made by the artist were meant to be reminders of what he had seen once he was back in his Paris studio.

Horses were a popular subject matter for French Romantic artists and many of Delacroix’s most quintessentially Romantic works depict galloping or rearing horses in the heat of battle. “I really must devote myself to rendering horses. I shall go to one stable or another every morning.” Delacroix closely studied their forms, both moving and standing still, as seen in the spontaneous pencil sketch. The pencil is used more freely than in the Moroccan sheet, although both drawings were done from life, and later used as inspiration for other more finished compositions.

Delacroix rarely depicted landscapes, but that aspect of his work is represented here by a strong, aggressively sketched pencil drawing depicting the wooded section of George Sand’s famous garden at Nohant, a favorite spot visited by the artist at least three times in the 1840s. Probably sketched outside, this drawing is a study for a watercolor of the same subject in the collection of the Musée de la Ville de Paris. By varying the weight of the pencil and the breadth of the lines and shading, Delacroix gives us an apt portrayal of the light falling on the winding road in the woods.

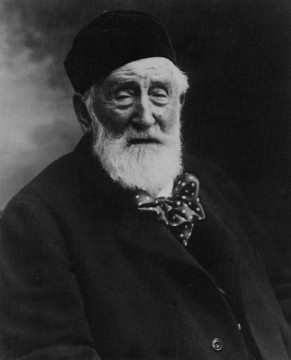

J-B-C Corot’s (1796-1875) large late charcoal drawing demonstrates the evolution of the artist’s stylistic journey. Early drawings by the artist, such as the small intimate sketch of his father, shown here as well, were typically done with a fine pencil, relying on line to describe subject matter. As his career developed, Corot’s line softened and began to blur, paralleling what occurred in his painted works. The late drawings become tonalist expressions or abstract renditions of the original subject matter, although, as though to retain a narrative element, Corot often placed, as he did here, a lone traveler in the composition, traversing the landscape perhaps as a symbolic representation of the artist who often walked many miles before planting his easel.

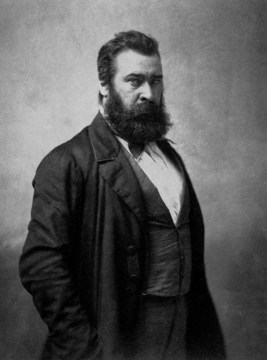

Antoine-Louis Barye (1795-1875), almost an exact contemporary of Delacroix , was a sculptor and painter known for his close observation of wild animals such as tigers, elephants, and large snakes. Likewise a prolific draughtsman, Barye made tracings of his own drawings in order to imagine new compositions for other works. This Reclining Tiger is one of the best examples of the how the artist merged abstraction and representation to show us the tiger rather than literally describing it. The sinuous line forecasts the work of later artists such as Matisse, who was also a sculptor.

Alfred Sisley (1839-1899) was a committed pleine-aire artist following in the footsteps of fellow impressionists Renoir and Monet. In 1880 Sisley and his family moved to the small town of Moret-sur-Loing near the forest of Fontainebleau, and some of his most successful works are depictions of the bridge in the center of town. Our pastel, one of only 70 recorded, is a view from the artist’s home and shows the railroad station in Moret, a spot likely to have been very familiar to the artist.

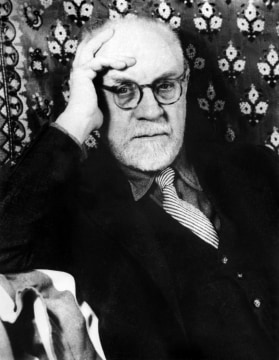

Henri Matisse (1869-1954) was also a prolific draughtsman who by 1940 was using a sinuous and elastic line to depict subject matter. Often drawing with india ink, Matisse’s technique eliminated all non-essential detail, so that the viewer could focus on the figure in space. This act of the extreme simplification of form culminated in the late paper cut-outs which were done in the years directly after our drawing.